Note: This assignment and some of its language is adapted from one published by Joseph Longhany.

The Assignment

Write a literacy narrative about the events and people that shaped your feelings and ideas about reading and writing. Recommended length: 800-1,200 words or more.

Assignment Goals:

- Develop a more robust writing process; experiment with prewriting/writing-to-learn/exploratory drafting strategies,

- practice with idea-development and alternative outlining strategies,

- experiment with Observation-Implication-Conclusion paragraph structures,

- practice using detailed description as evidence supporting a claim,

- practice with robust revision,

- practice with editing and polishing strategies.

This assignment asks you to a) investigate your past experiences with reading and writing, b) compose stories about moments and situations that shaped your perception of yourself as a reader and writer, c) compare your own experiences to those of others, and in so doing, d) arrive at a point that you would like to make about your literacy history.

What’s a Literacy Narrative?

Literacy narratives are first and foremost stories. So you’ll need some plot events and some characters to build your story with. This is non-fiction, so rather than making up your plot and characters, you’ll need to find them in your memories. With a little digging, all of us can recall events where we experienced growth or conflict around reading and writing. Very likely, particular people –relatives, teachers, librarians, mentors – played important roles in your literacy history. Writing scholar Deborah Brandt calls these people “literacy sponsors,” because their investment in our literacy shapes our feelings about reading and writing. According to Brandt, literacy sponsors “set the terms for access to literacy and wield powerful incentives for compliance and loyalty. Sponsors are a tangible reminder that literacy learning throughout our history has always required permission, sanction, assistance, coercion, or, at minimum, contact with existing trade routes” (166-167).

Here’s an example of a very short literacy narrative about one of my literacy sponsors:

I remember vividly being 8 years old and going to the local library with my mother. I was a voracious reader and had pretty much exhausted the offerings in the children’s section. Mom went to browse in the adult section, while I started to graze in the young adult section. I must have looked out of place, because the librarian told me in no uncertain terms that the children’s room was upstairs, and that I should high-tale myself up there right away. Our library was so small, Mom was close enough to hear this exchange and came to my defense. “He’s read just about everything you have up there,” Mom said with an edge in her voice. “He’s going to browse wherever he wants to in this library. I’ll check out whatever books he wants on my card.” The poor librarian didn’t say a word, and left me alone after that. I knew then that the only constraints on my reading would come from my interests, rather than what some expert thought was appropriate for my age. I had “permission” to ignore the library’s rules, and discount the views of adults.

What’s the Point of Writing a Literacy Narrative?

By looking back on the events and people that shaped our sense of ourselves and readers and writers, we can come to understand something about how our literacy history shapes our present attitudes about reading and writing. For example, one point of my story about my mother’s confrontation with the librarian is that my age and appearance misled a librarian to apply potentially harmful limits to my reading. I can imagine the same kind of “reader profiling” happening to other people with other identities and appearances. Without a defender to protect my access to books that would challenge me, I fear that my love of reading might have been stunted, thereby potentially changing my life’s trajectory in limiting ways. To phrase this more generally, our early literacy experiences can set us on life-defining paths, so literacy sponsors need to be very mindful about their interventions.

How to Get Started: Prewrite

Prewriting is the process of generating ideas to write about. It’s a great way of overcoming reluctance to write (aka. “writer’s block”), and can kick start your writing by generating lots of possibilities Begin by freewriting for five to ten minutes about your current feelings (good, bad, indifferent, or ambivalent!) about reading and writing. Then ask from which events, experiences, and people those feelings came. Mine your memory for important moments and situations that helped you develop your feelings regarding reading and writing. To help you excavate your memories, brainstorming answers to these questions, some of which Professor Longhany asked his students:

- What is your earliest memory of reading and writing?

- How did you learn to read and write?

- How did you come to identify certain values with reading and writing?

- What kinds of reading have you done in your past and what kinds of reading do you do now?

- Which teachers do you remember from your past who had a particular impact on your reading and writing?

- What is your current attitude towards reading and writing?

- Were there any aspects of reading or writing that frustrated you as you grew up?

- How have institutions impacted your reading and writing?

- How much have you enjoyed particular kinds of reading and writing that you did in your past? Why?

- Has there ever been a sense of reward or punishment associated with reading or writing from your past?

- What from your past has made you the kind of reader and writer you are today?

- What moments from your past do you remember as particularly empowering or dis-empowering?

- What do other people’s words and actions say about reading and writing, both positive and negative?

- How is reading and writing portrayed in films and stories about young people?

Write answers to these questions in any format—list, bullet point, concept map, phrases— that makes it possible for you to dig into your past. You could even tell the stories out loud – just be sure to record yourself, or if you have a recent Mac computer, use the voice dictation program to capture your memories. The main thing is capture a lot of ideas, without worrying if they “sound” good to a reader.

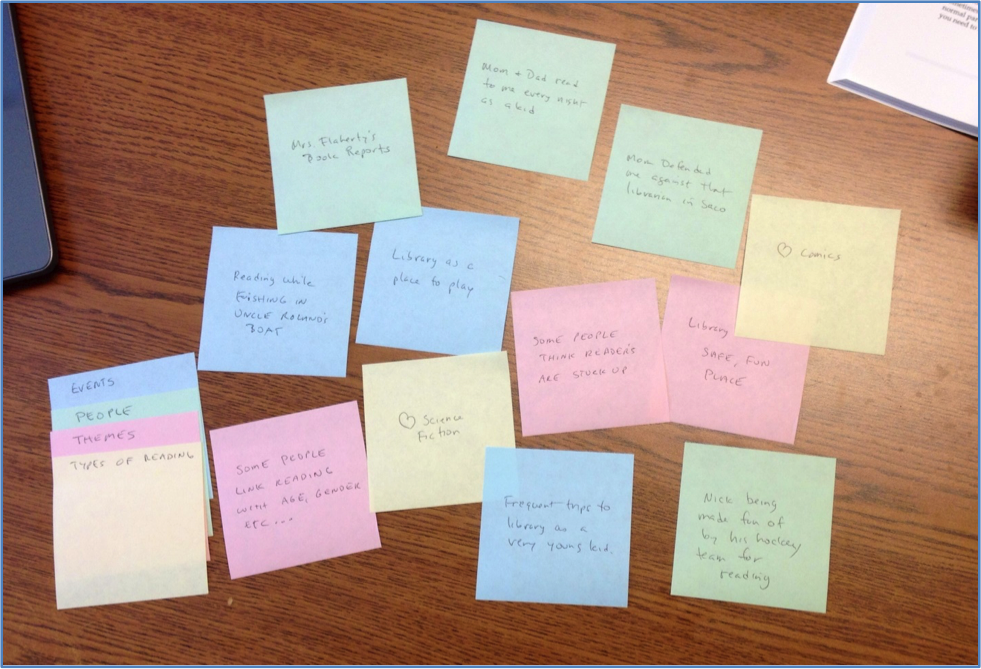

Here’s a set of sticky notes I used to generate ideas while doing this assignment.

STOP HERE: GO DO SOME PREWRITING. TRY MORE THAN ONE STRATEGY. ONCE YOU HAVE A BUNCH OF MATERIAL TO WORK WITH, CONTINUE ON.

Moving from Prewriting to Exploratory Drafting

Once you have generated material write about, it’s time to start thinking about how to organize it and begin writing an exploratory draft of your literacy narrative.

Rather than telling readers everything about your literacy history, sort through your prewriting material and find the events and people that feel most significant to you as you seek to explain the origins and development of your current feelings about reading and writing, and focus your draft on them.

As you consider what all these memories and experiences suggest, you should be looking for an overall “so what?” – a main theme, a central “finding,” an overall conclusion that your consideration leads you to draw. It might be an insight about why you read and write as you do today based on past experience. It might be an argument about what works and what doesn’t work in literacy education, on the basis of your experience. It might be a resolution to do things differently or to keep doing something that has been working. It might be a description of an ongoing tension or conflict you experience when you read and write—or the story of how you resolved such a conflict earlier in your literacy history. Or it could be a lot of other things. You could:

- Tell the story of your development from your earliest memories to later ones with the goal of explaining where your current attitudes about reading and writing came from. Along the way, highlight the most significant turning points of your history.

- Choose materials from your pre-writing that reveal the role that a person or type of person played in your literacy development.

Now’s the time to explore your literacy history to figure out what it means to you. So experiment and see what you can say about your experiences; don’t worry too much about getting it clean and polished.

PRO TIP: At this point, getting your exploratory draft done depends on two things: 1) how well you have used the prewriting process outlined in this guide, 2) how persistent you are in sitting in a chair without distraction in front of a computer and banging out words without worrying about how well they’re going to work in the last stages of the project. Emerging writers often quit too early in their writing sessions, before they’ve had a time to warm up and get their writing neurons activated. Don’t let yourself give up after 20 minutes. Work in 75-90 minute sessions and continue writing (freewriting if necessary) until you get into the “flow.”

STOP HERE: GO WRITE AN EXPLORATORY DRAFT. ONCE YOU HAVE A DRAFT, CONTINUE ON.

Revision: Focusing and Developing the Ideas of Your Exploratory Draft

At this stage of the process, you have written a draft of your experiences that says a little of what you want it to. But, if you’re anything like me, your draft is all over the place. Maybe you remembered something awesome in the middle of the draft and stuck it in there, but it doesn’t seem to fit, even though it feels important. Maybe you started telling one part of the story and got stuck and so started telling another part of the story, and that didn’t really work out the way you thought it would, and you can’t figure out how to make it work. The whole thing’s a mess and you never want to see it again.

The most important thing to know is that this state of affairs is a normal part of the writing process. Writing yourself into (and out of) corners is going to happen to you a lot when you use writing to think. Embrace the idea that early in the writing process you write to discover what you want to say, rather than writing to express what you already know.

Now is the time for revision. You’re probably used to thinking of revision as adding and subtracting a few lines here and there to add evidence or get rid of unclear ideas, to improve flow or style, or to correct errors in grammar, spelling, and word choice. But revision literally means envisioning your ideas and experience anew. And the only way you can really make sense of your experience is to think long and hard about it in a staged procedure that allows your thinking to grow. Fixing a paper is editing and polishing. That will come later, when your ideas are well-developed and expressed. Now, you need to grow your ideas and come to a better understanding of your experiences, and find the point of your essay.

When you revise, you add and subtract big chunks of the paper, add and subtract pieces of evidence, reconsider what your evidence means, and your ambitions for the paper. The best way to do that is to put aside the desire to write towards the final paper for a while and work on developing your ideas by returning to activities that look quite a bit like prewriting. Once you better understand your evidence, you can return to drafting.

Here’s what to do: As you read your exploratory draft, look for the words and phrases, events and ideas that seem to have potential even if they aren’t fleshed out yet, or don’t yet make sense to you. If you think they could be worth building on, even if you don’t yet know why, collect them on a bunch of sticky notes. Write one idea or event or person per sticky note. Be sure to write clearly, big, and in capital letters. As you generate your sticky notes, play around with them. Sort and resort them to see what connections you can make. Cluster them around categories, themes or ideas to see how they might fit together. Use your phone or camera to take photos of promising clusters of notes. Do some more freewriting on those ideas to see if you can uncover more details, or see connections between pieces. Add sticky notes as you go.

This probably seems like a messy process and it is. That’s because it’s creative. You need to free your associative brain from the need to produce clean, clear sentences in order to allow it to see patterns and make connections. Skip the developmental phase of the project, and you risk stalling the development of your ideas.

Cluster Your Experiences Around Ideas

Through this messy process of sorting your experiences, you’re likely to make connections that you otherwise wouldn’t, and to start seeing the point you want to make by telling your story.

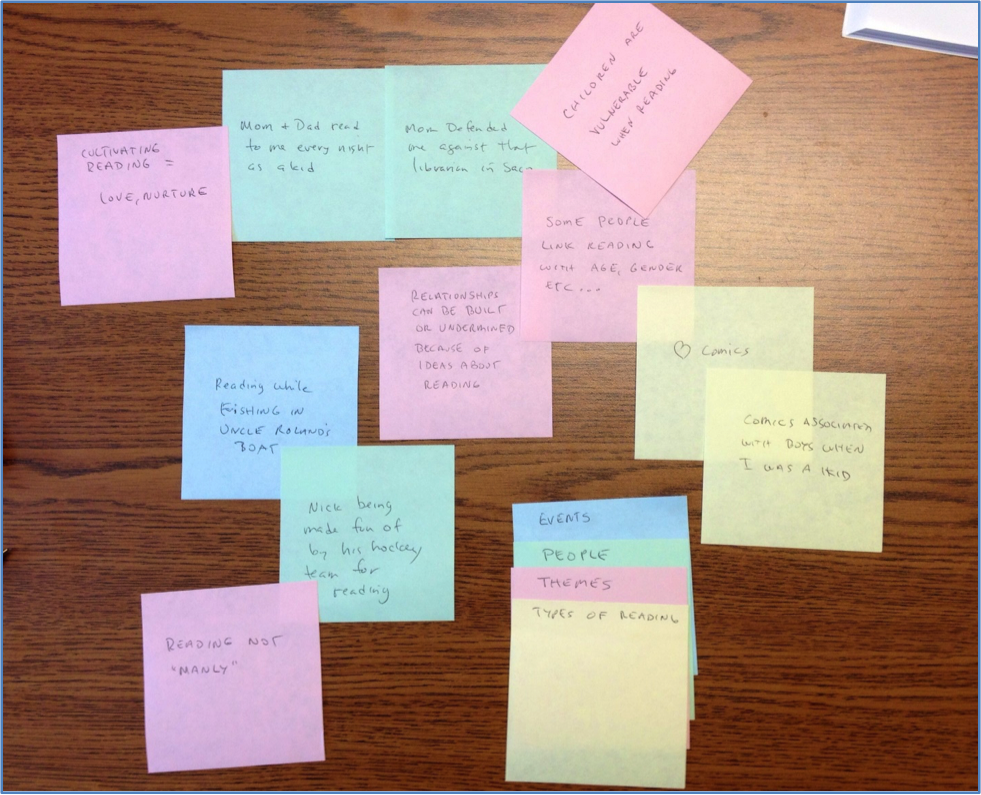

The first thing to notice about this photo of my sticky notes is that not all of my brainstorming material is included. Also notice that I added some new sticky notes (mostly pink “Theme” notes) as I made more sense of my experiences.

My sorted sticky notes ended up focusing on the idea that even while we’re gaining literacy, we’re forging relationships with people. As I thought about my literacy experiences with relatives, librarians and peers, I discovered that what we read and write shapes how people look at us, and, conversely, that how people look at us and who they think we are shapes what they think we ought to read and write. And when the conversation is about what children should read and write, things get tense real quickly. That’s an interesting observation about the role of literacy in our lives. One that, even though it’s not yet fleshed out, is worth building a paper around.

STOP HERE: GO FOCUS AND DEVELOP YOUR IDEAS. ONCE YOU HAVE A POINT WORTH PURSUING, CONTINUE ON.

Architectural Outlining: Rough Out the Structure that Supports Your Ideas

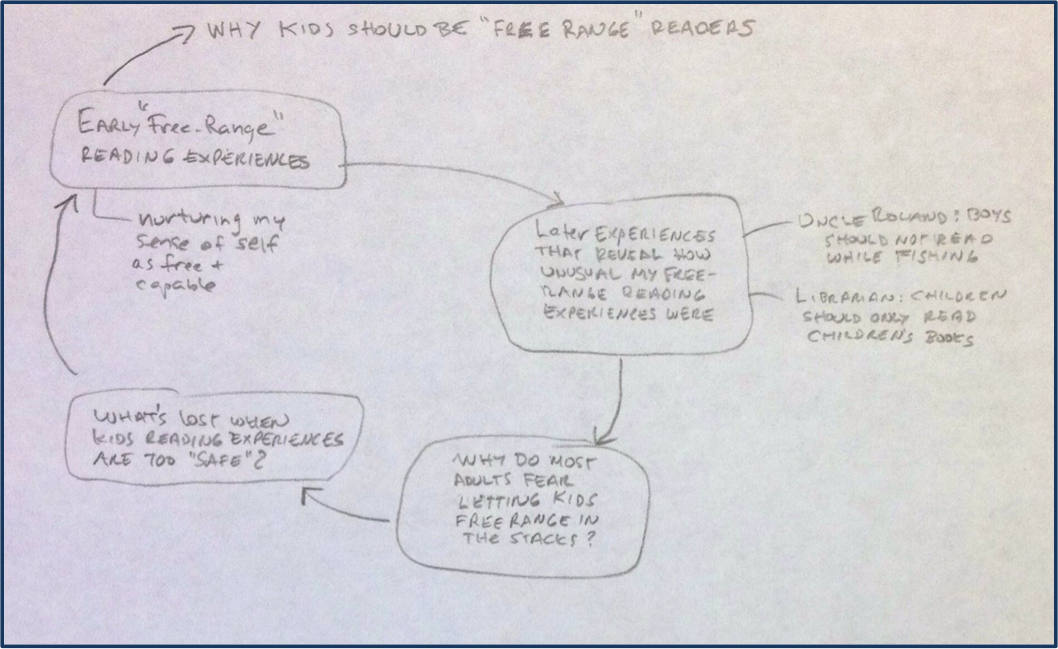

When you arrive at an observation like this one, you’re ready to write a rough outline of a draft focused on explaining what you learned by developing the ideas of your exploratory draft. Your essay will use descriptions of experiences and people as ways of helping people understand the ideas about literacy you want to convey. My sorted sticky notes connect experiences (blue) with people (green) and ideas (pink). The blue and green notes provide evidence in support of the ideas on the pink notes.

It’s possible that your sorted sticky notes can already serve as a rough outline of your essay. If not, you might want to rough one out. At this stage of the process, I recommend structuring the outline around the ideas you want to convey, rather than the events you want to relate, or the people you want to describe.

Your rough outline can be a short “nutshell” paragraph containing the seeds of some ideas, like this one:

My early literacy experiences helped me forge nurturing and empowering relationships with people that made me feel secure in my emerging sense of self. My parents’ commitment to reading to me every night at bedtime, and the freedom I had to choose what I read are key here. Later experiences showed me how rare my freedom was. Uncle Roland thought that boys shouldn’t read while fishing, and that librarian thought kids should only read children’s books. I wonder why so many adults are afraid to let kids free-range in their reading? What gets lost when kids aren’t allowed to follow their interests and read only what adults think is safe or appropriate for them?

Or a visual nutshell:

But it shouldn’t be a classic numbered-lettered outline, because at this stage, you’re still working to figure out what you think, and committing yourself to such a tight outline will discourage you from allowing your ideas to grow.

Roughing out a structure without too much detail can make drafting much easier, while allowing for your ideas to grow and develop. I don’t necessarily know the answers to the questions in the outlines, but I’m sure that I’ll be able to work towards answers in my next draft.

You’re first crack at making a rough outline might not work, but it will certainly move your thinking forward. Don’t be satisfied with just “getting the homework done.” Work to solve the problem at hand, which is to find a structure that will support your drafting efforts. Try out several different outlines and persist until you think you have something that you’re pretty sure will work.

STOP HERE: GO FOCUS AND DEVELOP YOUR IDEAS. ONCE YOU HAVE A ROUGH OUTLINE, CONTINUE ON.

Writing Within Your Design Using Observation-Implication-Conclusion

With a rough structure in place, it’s time to go write a new draft. That’s right, a new draft. You shouldn’t try to fix your exploratory draft. It has done its work helping to generate ideas, and the effort to fix it would be counter-productive. It’s OK to use small fragments from prewriting or your exploratory draft, but you really want to generate new sentences and paragraphs, one’s that work with the purpose and design you discovered in your development and outlining procedures.

But, remember, in this later-stage draft, you have already found the ideas you want to convey. You don’t want to get side-tracked. So work architecturally, by building segments of the essay with attention to the larger design you have in mind. You should allow your ideas to expand within the design you arrived at through the rough outline, but set aside for another paper ideas that emerge that can’t be accommodated within your design.

With a structure built around ideas, some events and characters to use as evidence, and bits and pieces of earlier drafts and prewriting activities to draw on, you’re ready to write a draft that should say quite a bit of what you want to say.

At this point, it’s undistracted, focused seat time that’s going to get the work done. With all the prewriting and idea-development work you’ve done, you should really aim to get a full draft of this short paper done in one sitting. In this sitting, focus on getting the ideas and pieces of evidence from your literary history in place and figuring out what they mean to you, even if it’s just in skeletal form. You can always flesh out the details in a later session.

One of the best ways to tie bits of story together with your ideas, is to use an Observation-Implication-Conclusion paragraph or paragraph-sequence structure.

The Observation-Implication-Conclusion (OIC) paragraph structure is just a little more complex than the Idea-Illustration-Comment paragraph structure you may be used to. It’s valuable, because it allows you to draw more complex connections between your evidence and the ideas and claims that make sense of your evidence. Here is an explanation of the moves to make in an OIC paragraph (or paragraph-sequence), with some samples.

Observation: What’s your evidence? What specific parts of your experience do you focus on when you look at your literacy history? Why? What patterns do you see?

Moves: Tell stories, describe people and events. Focus readers’ attention on significant details that you will comment on later in the paragraph. Hint at the implications coming later. In non-narrative essays, explain explicitly why you chose those particular aspects of your experience to focus on. In narrative essays, you can be more subtle.

Example: Not all of my early reading experiences were nurturing. Each summer, my Uncle Roland invited my father and one of his three sons on a fishing trip. When I was nine it was my turn. My brothers had told me what a great time they had. Uncle Roland was funny and he really knew how to catch fish. Great fun, right? Well, being me, I put three thick science fiction books in my pack in case I got bored. Well, about half an hour into the fishing trip I got bored. It’s true that Uncle Roland was funny. In fact, I’m sure now that his off-color jokes were meant to signal to me that I was old enough to be treated like a “man” and not a “child.” And we did catch fish. Well, Dad and Uncle Roland did. Me, not so much. Why? Because I sat there in the bottom of the boat, fishing rod resting on the side of the boat, my nose in a book, and not paying much attention to the subtle signals traveling up my line. “What’s the matter with you?” Uncle Roland asked. “Don’t you want to catch fish? Put that book away and pay attention.”

Implications/Insights: What can you say about your experience/evidence that will help other people understand it better and see it as support of an idea or claim [about literacy]?

Moves: Put your experience in context: how usual or unusual is it? Point to significant details of your experience/evidence and explain what’s interesting, strange, or revealing about them? Reveal the implicit in the explicit by naming and explaining the ideas, concepts or values that are suggested by your emerging understanding of your experience/evidence. Blend implications with looks-back at the evidence.

Example: I’m sure Uncle Roland meant to be helpful. In his mind, he was initiating me into an important experience that would help me become a man. But not just any man, the “right” kind of man, the kind of man that he was. Don’t get me wrong, Uncle Roland was a voracious reader. He was self-educated; he read widely, and not only in plumbing and heating systems, which was his business. He read history and politics. But he didn’t have much time for literature. His success as a business man was a product of native intelligence and the insights and ideas he gained from his reading. But it was equally a product of his aggressive competitive approach to business. Looking at me, sitting there, most of my mind parsecs away in a piece of science fiction, letting fish off the hook, he must have thought that my devotion to reading wasn’t quite manly enough. That if I was to be successful in life, my interest in reading needed to be tempered by an interest in the world beyond me. My Dad looked at me, and I put my book down and tried to focus on fishing. But what I really wanted to do was get back to the adventures of Valentine Michael Smith in Stranger in a Strange Land.

Conclusion: What tentative generalizable claim(s) [about literacy] does your well-understood experience/evidence support?

Moves: Formulate and explain the implications of your implications by drawing a conclusion that could apply to similar evidence or cases other than the one that started the paragraph/sequence. Blend conclusions with looks-back at the evidence. But as the paragraph comes to a close give priority to the more general claims.

Example: That day passed, but it sticks in my mind almost 40 years later. Uncle Roland surely meant to be kind, and to tell the truth, I don’t think I let his criticism affect me much, despite how much I admired him. But I wonder how many other kids, less secure in their devotion to reading, might have been put off by his remark, and thought something was wrong with them when an admired relative or mentor shamed them for reading. Kids find adult sponsors of literacy everywhere. And because they care for kids, adults often feel entitled, even obligated, to project their ideas about reading and writing on them. Despite his own experiences of reading, my Uncle Roland feared that what he saw as my overinvestment in reading, especially the made-up worlds of science fiction, would make me unfit for success in a real world where men used their wit and strength to compete with one another. I did OK. But adult sponsors of children’s literacies should be mindful of how their own hopes and fears shape their approach to sponsorship. Adults engaging children in literacy activities should aim to support the child’s emerging sense of self, rather than steering them in a direction that meets the adult’s expectations.

Not all of your paragraphs in an essay will take this form, but many will because of its power to blend description of your evidence with narrow, case-based, implications and insights that come together in more general claims about your topic in a conclusion. Notice, too, that OIC can provide the structure both a single paragraph or for a series of paragraphs. Experiment with OIC in your draft.

GO WRITE YOUR ESSAY. WHEN YOU HAVE A FLESHED OUT PIECE, CONTINUE ON

Editing, Polishing, and Proof-reading

By this stage, you should have a pretty solid draft that:

- Tells a story,

- Draws out the implications of your literacy experience,

- Makes a point

The last step is to make the paper communicate to readers the best it can. It’s time to polish, edit and proofread. I’ll define each of these terms here, but for detailed strategies that enable you to see the problems in your own paper, consult the Editing and Proofreading page at the Gustavus Adolphus College Writing Center webpage: https://gustavus.edu/writingcenter/handoutdocs/editing_proofreading.php

Editing

When you edit, you’re assessing each paragraph of the paper from a reader’s perspective. You’re looking for moments in your essay that might leave your reader confused or unsure of your point because:

- You have left out necessary details

- You have chosen wrong or ambiguous words

- Sentences in paragraph are out of sequence logically or in terms of action

- Concepts are undefined

- Your explanations don’t go far enough

- You haven’t explained why a reader should care

- Your point isn’t explicit

Polishing involves adding, subtracting, and changing words, phrases, sentences, and occasionally paragraphs. Here you’re still working on getting the ideas right, and expressed well enough that your meaning will come through to a reader.

Polishing

When you polish, you’re assessing each paragraph and sentence from a reader’s perspective. You’re looking to improve word choice, style, clarity and precision. At this level of finishing, you’re concerned with both with making sure that readers get your meaning, and making your paper easier and more appealing to read. Look for moments where:

- The level of complexity of your sentence structures doesn’t match the level of complexity of the ideas you’re trying to express,

- Paragraphs are missing a beginning, middle, or end

- Paragraphs are not connected to one another via topical transitions

- Your language choices convey unconscious bias,

- Your language choices create a negative impression of you,

Editing involves adding, subtracting, and changing words and phrases, and occasional sentences.

Proofreading

When you proofread, you’re assessing the correctness of each sentence.

Look for the following kinds of errors:

- Missing Title

- Wrong word

- Spelling

- Mixed constructions

- Missing words

- Missing or incorrect documentation

- Missing signal phrases

- Unnecessary or missing capitalization at the beginning of sentences or in titles

- Missing or unnecessary commas, comma-splices or fused sentences

- Subject-verb agreement

- Shift in tense

- Fragmented sentences

In order to see these errors in your paper, you have to disrupt your ordinary ways of reading. Try

- Reading out loud

- Reading each paragraph sentence-by-sentence from the last sentence to the first.

- Looking for one type of error at a time

- Printing the paper in a larger font (l16 or larger pt)

![SASC - Student Academic Success Center - UNE [logo]](https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.uneportfolio.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2022/02/SASCLogoSquare_Smaller-3-e1644936452801.jpeg)